Real-World Treatment Patterns in Bipolar Disorder

A large retrospective claims analysis found that real-world treatment practices for bipolar I disorder (BP-1) may often diverge from evidence-based guidelines, with antidepressants and benzodiazepines frequently prescribed despite guidelines advising against their use as first-line therapy.

In this large-scale, retrospective claims analysis, Jain et al identified a potential discordance between real-world prescribing patterns and current evidence-based guideline recommendations for bipolar I disorder (BP-1) in the United States. The study showed frequent use of antidepressant monotherapy and benzodiazepines despite their limited role in guideline-recommended care in BP-1. It reflects a clinical practice gap that may contribute to suboptimal patient outcomes.

Study Rationale

Bipolar I disorder (BP-1) is a complex, chronic, and often severe mood disorder characterized by alternating episodes of depression and mania or mixed features that can carry significant challenges in diagnosis and long-term management.1 Despite guideline-driven recommendations for BP-1 treatment, real-world data describing longitudinal treatment patterns in clinical practice remain limited.2

Misdiagnosis can be common in BP-1, particularly as patients tend to present clinically during a depressive episode. As such, studies have shown that patients may be misdiagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) for up to five to 10 years, which may lead to inappropriate antidepressant initiation.3,4 Antidepressant monotherapy has been shown to exacerbate mood instability in patients with BP-1, increasing the risk of manic switching as well as rapid cycling.2

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of atypical antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or adjunctive therapy (ie, a mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic) for BP-1 depression. For BP-1 mania, guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics as monotherapy. In severe cases, a combination of both may be used. Guidelines advise against the use of antidepressants as monotherapy in BP-1 depression, listing them as a fourth-line therapy as an adjunct to mood stabilizers, and they are not included in the recommendations for BP-1 mania.2

Clinical practice guidelines are designed to help providers make informed and evidence-based treatment decisions; however, surveys of practicing psychiatrists reveal high rates of unfamiliarity with and nonadherence to published guidelines.1

To address this gap, Jain et al sought to quantify real-world prescribing trends among patients newly diagnosed with BP-1 across multiple episodes and lines of therapy (LOTs) within each episode, and how they compare to current clinical practice guidelines.2

Study Design and Methodology

Using the IBM® MarketScan® Commercial Claims database, the study investigators retrospectively analyzed real-world medication treatment patterns among adults with newly diagnosed BP-1 or bipolar II disorder (BP-2) between 2016 and 2018.2 This clinical article summary will focus on the BP-1 subset of patients.

Key inclusion criteria included2:

- At least one inpatient claim with a primary diagnosis or one outpatient nondiagnostic medical claim with an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) diagnosis code for BP-1, and

- 12 months of continuous enrollment before (baseline period) and 6 months after their initial BP-1 diagnosis (follow-up period). The index date was the date of BP-1 diagnosis after the baseline period.

Medication regimens were characterized by class (eg, mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, typical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, stimulants, and others). Continuous treatment periods based on filled prescriptions were segmented by LOTs, and episodes were characterized by mood polarity based on diagnosis codes (depressive, manic, mixed).2

Study Findings

A total of 36,587 patients received treatment for any type of initial BP episode. There were 2,067 different individual regimens, and the top 10 accounted for 43% of the regimens.2

The most common treatments among the top 10 regimens were monotherapies: a mood stabilizer (9.6%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (6.9%), and benzodiazepines (6.9%).2

Figure 1 shows the distribution of first-line treatments (LOT1) across all patients.

Figure 1. LOT1 monotherapy and combination therapy medications during first episodes for all patients.2

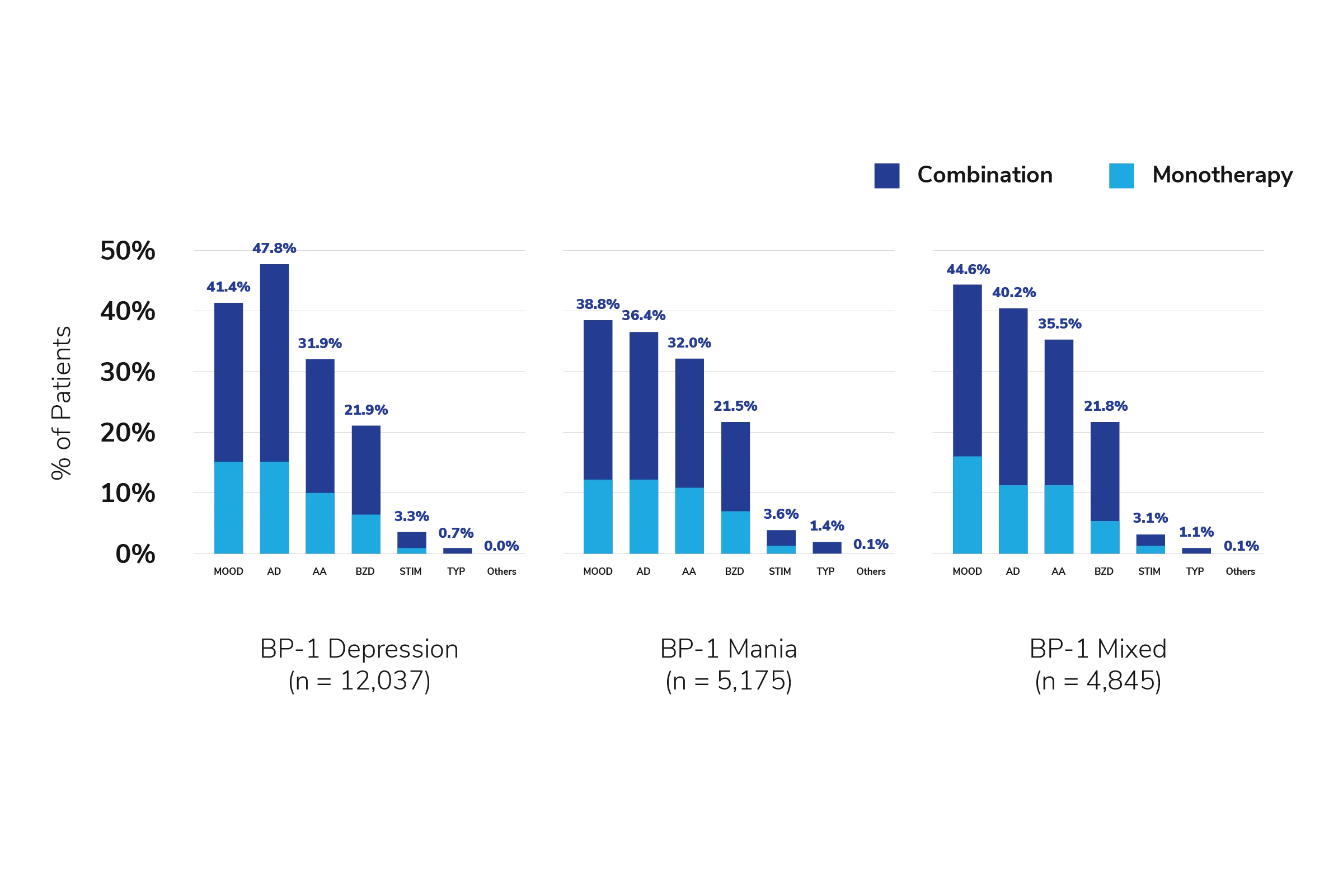

Figure 2 shows the distribution of LOT1 by episode type. The most common initial BP-1 episode types were BP-1 depression (29.8%), BP-1 mania (12.8%), and BP-1 with mixed features (12%).2

Figure 2. LOT1 monotherapy and combination therapy medications during first episodes for patients with BP-1 depression, BP-1 mania, and BP-1 mixed.2

AA = atypical antipsychotics, AD = antidepressants, BZD = benzodiazepines, MOOD = mood stabilizers, STIM = stimulants, TYP = typical antipsychotics.

Widespread Use of Non-Guideline Therapies

In the initial treatment phase (LOT1), 43.8% of patients received mood stabilizers, 42.3% received antidepressants, 31.7% were prescribed atypical antipsychotics, and 20.7% received benzodiazepines—often in various combinations (Figure 1). The most common medication classes in subsequent LOTs were antidepressants and benzodiazepines.2

In LOT1 of their first episode, only 12% of patients with BP-1 depression and 22% with BP-1 mania were managed with the guideline-recommended first-line therapy. Medications and medication combinations were heterogeneous among patients, and there was substantial variability in the number of treatment patterns across LOTs, suggesting that many practitioners are not using evidence-based prescribing practices.2

Current guidelines include atypical antipsychotics in the management of BP; however, only about one-third of patients in the study were prescribed atypical antipsychotics.2

Persistent Use of Antidepressants

Antidepressants were prescribed to approximately 50% of patients during a depressive episode of BP-1, and approximately 15% of patients were on antidepressant monotherapy in LOT1, despite guidelines recommending against the use of these medications as monotherapy in BP depression.2

The use of antidepressants is also not recommended as first-line treatment or as monotherapy in patients with BP-1 mania, but over 36% of patients were prescribed antidepressants, and 12% were on antidepressant monotherapy for their first-line treatment.2

Benzodiazepines Commonly Prescribed:

Benzodiazepines were prescribed in about 20% of patients with BP during LOT1 and persisted in subsequent LOTs, despite guidelines limiting their role to adjunctive use for acute mania.2

Frequent Changes in Treatment

Roughly 90% of patients received at least one pharmacologic treatment, and about 80% went on to receive a second line of therapy (LOT2).2

Study Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with limitations. The study relied on administrative claims data, which may lack detailed clinical information such as symptom severity, adherence, and reasons for medication changes, and introduces the potential for data coding and/or entry errors (eg, missed or misclassification of BP episode types, comorbidities, or medication use). Further, the analysis was based on filled prescriptions and excluded inpatient medications and unfilled prescriptions. In addition, the study was limited to commercially insured populations, which may potentially limit generalizability to Medicaid, Medicare, or uninsured populations. Lastly, some medications included in the analysis are used for multiple conditions, such that the diagnosis for which the medications were prescribed could not be precisely determined for all cases. Thus, it is possible that the antidepressants may not have been prescribed with the intent to treat BP and were prescribed for other uses.2

Clinical Relevance of Findings

This study suggests there may be an incongruence between current prescribing patterns and current guideline recommendations, and its findings highlight the importance of aligning clinical practice with established treatment guidelines for BP-1.

In particular, antidepressants were frequently prescribed in BP-1 despite guidelines recommending against their use as first-line therapy. Antidepressant therapy is recommended as a fourth-line option, adjunctive to mood stabilizers, for BP-1 depression and is not recommended for BP-1 mania.2,5,6

Future Research Directions

The study by Jain et al provides compelling evidence of the current clinical treatment-pattern landscape and discordance with clinical guideline recommendations in BP-1. Future research should focus on improving adherence to and uptake of guideline-recommended treatment regimens for BP-1 in day-to-day practice.2

Provider's Insights on the Potential Clinical Implications of the Study

1) What factors might be contributing to the high rate of inappropriate antidepressant monotherapy use in patients with BP-1?

"It's difficult to say why so many antidepressants are used in BP-1. Some healthcare providers may be more comfortable prescribing antidepressants due to their safety profiles. The combination of clinician and patient familiarity may be why physicians are choosing antidepressants for BP-1 despite guidelines recommending against it."

2) How can practitioners address the gap between clinical guideline recommendations for treating BP-1 and real-world prescribing patterns? How can they help improve the uptake of clinical practice guidelines?

"I think a significant part of the problem is that some of the major guidelines in psychiatry are updated infrequently, and as a result, most guidelines tend to be fairly outdated. Consequently, some healthcare providers may not feel as much urgency to keep up with them and follow them as closely as in other specialties of medicine. However, certain core principles, such as cautioning on the use of antidepressants, are so well established in guidelines, and the evidence for that has not changed. Furthermore, some guidelines are updated more frequently but receive less attention, such as the Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines, which, in my opinion, are quite good. Overall, I think we need to take the guidelines that are available and utilize the evidence-based practices out of those that were present at the time. Then, as clinicians, we can use our best judgment as to how to update those based on evidence that has emerged since those guidelines were published."

3) Given the common use of antidepressants, how do you approach mitigating the risk of inducing mania in BP patients in clinical practice (to help mitigate the risk of inducing treatment-emergent affective switch)?

"In actuality, the induction of mania in individuals with BP is still lower than most people think. That doesn't mean that there isn’t a potential risk with antidepressants, because there is evidence for a destabilization of the mood states with potentially more rapid cycling, more mood episodes, more irritability, and more dysphoria. Antidepressants are not a substitute for effective, evidence-based treatments. Antidepressant use in these patients may lead to more mood episodes, which may ultimately lead to progression of the disease. What I do is ensure that there is an antimanic regimen on board, such as the recommended mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics."

4) What strategies can be implemented to enhance treatment adherence and reduce the need for frequent medication changes?

"Medicine is always an art, and there must be a balance between efficacy and tolerability to help promote adherence. However, I think clinicians sometimes tilt the scales too far in favor of tolerability, sometimes leaving efficacy out of consideration. They may do this because they think that a person who is ambivalent about medication, which is often the case in BP-1, would not want to take medication that is giving them side effects. However, we must not forget that people certainly won't want to take medications if they think they're not working for them! Many cases of complex polypharmacy that I see are because each one of the medications that was incrementally added had minimal or potentially no efficacy. Therefore, more medications needed to be added, which can lead to a cumulative side effect burden and potentially impact treatment adherence."

Craig Chepke, MD, DFAPA

Craig Chepke, MD, DFAPA, is a board-certified psychiatrist and distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. He is currently the medical director at Excel Psychiatric Associates in Huntersville, North Carolina, and an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry at Atrium Health. Dr Chepke's clinical and research interests include serious mental illness, movement disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and sleep medicine, where he utilizes a person-centered care model to provide tailored treatments.

References

Gomes FA, Cerqueira RO, Lee Y, et al. What not to use in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of non-recommended treatments in clinical practice guidelines. J Affect Disord. 2022;298(pt A):565-576. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.007

- Jain R, Kong AM, Gillard P, Harrington A. Treatment patterns among patients with bipolar disorder in the United States: a retrospective claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2022;39(6):2578-2595. doi:10.1007/s12325-022-02112-6

- McIntyre RS, Calabrese JR. Bipolar depression: the clinical characteristics and unmet needs of a complex disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(11):1993-2005. doi:10.1080/03007995.2019.1636017

- Vossos H, Nwosu-Izevbekhai O. Mood disorders and rapid screening: a brief review. J Ment Health Clin Psychol. 2024;8(2):51-54. doi:10.29245/2578-2959/2024/2.1314

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2002.

- University of South Florida, Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program. Sponsored by the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. 2019–2020 Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults. University of South Florida; 2020.

This summary was prepared independently of the study’s authors.

This resource is intended for educational purposes only and is intended for US healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should use independent medical judgment. All decisions regarding patient care must be handled by a healthcare professional and be made based on the unique needs of each patient.

ABBV-US-02107-MC, V1.0

Approved 09/2025

AbbVie Medical Affairs